One objection to including the Documentary category in the previous years awards was the lack of exceptional documentaries to warrant enough nominations. Either way, there have been more quality feature documentaries released in the last six months and the demand is there to justify wider releases beyond a one-off screening at your not-so-local art centre. Documentary makers are also moving away from the personality-dominated films of Michael Moore and going towards telling stories; drawing closer to their subjects in order to get under their skin.

The results are emotional, inspirational, sometimes scary, but always powerful. To demonstrate this, I have selected three of my favourite feature documentaries released in 2011 so far that demonstrate why the art-form is experiencing a resurgence.

UK Release: 3 June 2011

Senna is enjoying a level of popularity usually reserved for big studio productions. Compared to other successful feature documentaries such as Supersize Me and Bowling for Columbine, Senna is unconventional. There are no talking heads, there is no authorial narrator and it’s compiled entirely of archive footage. Even the subject matter doesn’t have a broad appeal; Formula 1 is a sport, which is enough to put off certain people, and it’s about an individual who not everyone will recognise.

Despite all these factors, Senna still impacts those adverse to F1. Amongst the group I saw the film with, the followers of F1 were stifling sobs whilst those who couldn’t tell their Schumachers from their Mansells were also fighting back the tears. Senna was an extraordinary character with self-confidence of cinematic proportions, but it is also the composition of the footage and the score that gives the film a broad appeal. Together with the departure from what is considered elementary in a popular feature documentary, Senna should be celebrated for its innovative film-making, proving that audiences don’t need a celebrity constantly explaining what is happening on screen. Of all the documentaries released this year, Senna looks to be the biggest game changer.

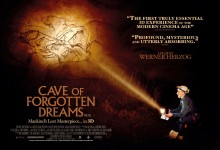

UK Release: 25 March 2011

Werner Herzog’s tour of the oldest known wall paintings in the Chauvet Cave in southern France is an example of how documentaries are expanding further into discussions on film-making techniques. In this case, it’s the 3D debate.

As critics hail the demise of 3D, Cave of Forgotten Dreams 3D (CoFD) is a glimmer of hope for the format. So far 3D has been synonymous with action sequences, in which CGI is crammed into every frame to make the viewer feel like they are on a roller-coaster. Now as the novelty is wearing off, 3D is becoming like the homes of many roller-coasters: gimmicky and plain nauseating. CoFD departs from this theme park aesthetic. Herzog uses 3D to enhance the viewer’s understanding of the cave’s artwork. Part of the beauty of these paintings is how they use the curves of the cave walls to suggest movement; depth becomes important to fully appreciating these paintings and 3D allows Herzog to achieve this. Rather than being a marketing ploy, CoFD demonstrates that 3D is an effective film-making tool when reasonably applied. This is an important aspect that should be considered before 3D is dismissed altogether.

CoFD is not only a useful case in the 3D debate; it is also a great documentary that captures the wonder and mystery of primitive artworks. Away from the issue of 3D there are cheesy moments, such as the New Age panpipes and the albino crocodile epilogue, but it is a fascinating insight into a subject matter that very few will ever encounter first-hand.

UK Release: 18 March 2011

Benda Bilili tells the story of a group of paraplegic musicians who rise up from busking on the streets of The Democratic Republic of the Congo, to packing out venues throughout Europe. The result is a story of humans overcoming their own physical shortcomings and social statuses through musical talent. There is more at stake here than wanting to be adored, these men are playing for the welfare of their families.

These ideas make the film sound melodramatic, but it isn’t. Benda Bilili! is subtly moving because the events aren’t over-dramatised, they are inherently dramatic enough. Veteran documentary-maker Albert Maysles said one fundamental aspiration in his films is to establish a common ground between the audience and the subject to build understanding. In this case, the group are humanised: we see them at their lowest as a fire destroys their home and their highest when they finally play to enthusiastic festival crowds. We can relate to them without feeling charitable pity or patronising joy. It’s a feel-good film with an emotional storyline, but stark reality prevents it from being soppy. This is real-life story-telling, a non-fiction drama film, and it’s very enjoyable.

So that’s my three favourite feature documentaries of the year so far. Whilst the “golden age” claims are a bit strong, these films point towards the brink of an exciting time for feature documentaries. Of course, there are those who don’t share this optimism. Television documentary-maker Molly Dineen, recently honoured with BFI reissues of her back catalogue, expressed her worry that as more documentaries are released in cinemas and on television, those with important stories will be crowded out. A fair warning, but in the meantime let’s make the most of an art-form that is going from strength to strength.

Written by Sam Lewis.